People pass judgment before they know the whole story. For example: A new student is added to one a route, and the driver immediately notice there is something different about him or her. The child may twitch nervously in their seat, or they may blurt out inappropriate comments without cause. What appears to be bad behavior is sometimes something that is uncontrollable, often times a disorder commonly referred to as Tourette’s syndrome.

“Tourette’s can sometimes look like very purposeful behavior,” said Susan Conners, an education specialist for the Tourette Syndrome Association (TSA). “Bus drivers are in a very unusual position because they’re on a school bus with 30 or 40 kids. If they hear one child make loud noises or say something that’s not appropriate, they may immediately assume that it’s a bad kid being disrespectful. If they don’t know the kid has Tourette’s, the kid is constantly going to be getting in trouble for something he or she can’t control.”

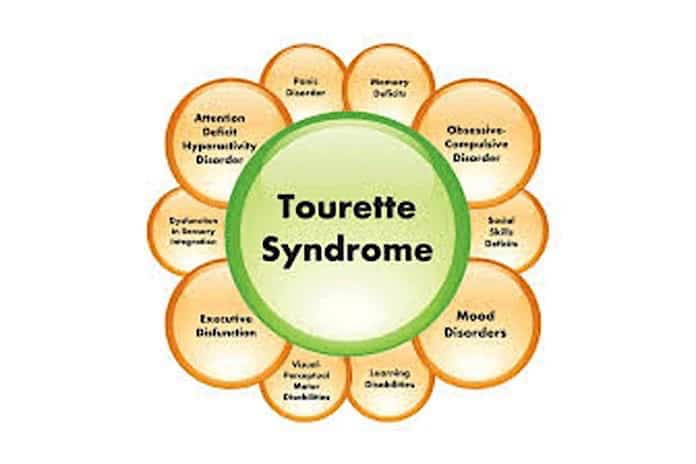

Tourette’s syndrome is a neurological disorder that is characterized by either involuntary facial, body or vocal tics that can become frequent, repetitive and rapid. They are completely outside of the individual’s control and usually surface in early childhood or adolescence. Although the disorder was first diagnosed in the early 19th century, there is still no specific cure and very little training to help pupil transporters with students prone to its effects.

“I decided to do in-depth training for my driver and monitor teams because they seemed to have many issues with their expectations of student behaviors,” said Cheryl Fitzgibbons, director of transportation for Southern Westchester BOCES in White Plains, N.Y. “They saw that on some days all of the stars aligned and a student had a good day, and then the other majority of the days the behavior was not so good.”

Fitzgibbons presented her crew with detailed information on a number of disorders, including Tourette’ss, and their characteristics. She also stressed to the drivers that certain tics and noises may be stress relievers for students, and asking them to stop the behavior usually causes more stress and increases in the actual tic or noise behaviors.

“We have found that, since we decided to really give a much more educational approach to this type of training, our conduct reports had been reduced dramatically — what our team viewed as a purposeful and controllable behavior in the past has been reset to a much better understanding of the behavior disorder and an appropriate behavior expectation,” added Fitzgibbons.

For Conners, training is key to understanding the behaviors associated with Tourette’s. The retired teacher from Williamsville, N.Y., understands the disorder on both a technical and personal level. Although she was not clinically diagnosed with the condition until she was 36 years old, Conners has suffered from it since childhood.

“I think its critical that the person understands what’s going on with the child,” said Conners. “Whenever I do an in-service at a school, I always ask them to invite the bus drivers.”

One of the more useful tips Conners offers drivers is encouraging children with the disorder to sit up front so the driver can be aware of any ridicule from other students. Many of those with Tourette’s also have sensory issues, making it difficult for them to control their tics in noisy and unstructured environments. For some students, Conners has suggested they put on headsets and ask the drivers to let them listen to music because it cuts out some of the noise in the background.

“The end of the day is also really tough for them because they’ve struggled so hard all day to stay in school and do the best they can, given all they’re dealing with. And then they get on the bus, and all the chaos and noise gets to them, and they fly off the handle instantly,” said Conners. “I tell the kids to try to tune out the world. But sometimes it doesn’t work.”

In one district she worked with, a bus with a mix of students from grades four through 12 made the experience even harder for a particular student. After some deliberation, the child was placed on a smaller bus with special needs students and was much happier because he could didn’t like riding on the larger bus and was always getting in trouble.

No matter what behavioral issues may exist for a student, there is one key component in trying to solve the problem: communication.

“We teach and practice patience, try to connect with the student any way we can in order to communicate, and we are careful observers when we seat students next to each other,” said Neal Abramson, director of transportation for Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District in Southern California. “The communication remains open between our drivers, school staff and the parents.”

Find out more on this disorder by visiting the Tourette Syndrome Association Web site at www.tsa-usa.org.

Reprinted from the February 2009 issue of School Transportation News magazine. All rights reserved.