Despite an apparent delay in new federal entry-level driver training rules, student transporters can build and even exceed requirements for a compliant safety culture

Safety is no accident. The phrase is an industry cliché for good reason.

“Every mother assumes that everything that can be done for safety on school buses is being done,” said Jeff Cassell, founder of School Bus Safety Company. “Most people take it for granted. But I can tell you [there are] school districts that say to me, ‘We comply with the regulations, we don’t need to do any more.’ The regulations are the minimum you can do. You can’t do any less, so you should really be doing considerably more.”

The new FMCSA entry-level driver training requirements that are required by the 2021 Moving Ahead for Progress Act (MAP-21) that was passed into law by Congress focus on qualifications, wellness, hours of service for truck drivers and whistleblower protection. They are also designed to ensure refresher courses for veteran drivers.

The new rules also mean implementing a safety management system in every commercial transportation organization.

The law was supposed to go into effect on Feb. 7, 2020. As of this report, the FMCSA was unofficially delaying the entire implementation by two years, a spokesman told attendees of the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation annual meeting in Washington, D.C. on Oct. 15. The agency initially sought to only postpone the technical requirements for an online database. Multiple attempts by School Transportation News to obtain an update from FMCSA were unsuccessful at this writing.

Still, Cassell advised that school districts and bus companies should be moving ahead with installing a compliant safety management program, if they don’t already have one.

The process begins with a safety management policy that is driven by leadership commitment and accountability. Safety risk management must identify, assess and mitigate risks, in tandem with the promotion of safety in communication and training.

Finally, a strong program is self-reflexive, with built-in methods of measuring, monitoring and evaluating the policies that are in place.

Cassell preaches creating a safety culture to identify and mitigate risks in day-to-day operations so that everyone will “do it right the first time.”

Although the American School Bus Council reports that students are 70 times safer traveling to and from school in buses than in passenger vehicles, one careless mistake can cost a child his or her life.

The National Safety Council reports that 3,000 student passengers were injured in 2017 during school bus-related crashes. While four students died, each incident was caused by one or more careless actions that should have been prevented.

Cassell argued that 99 percent of “accidents” stem from conscious decisions on the driver’s part. By identifying and avoiding 22 risky behaviors, he said that accidents can all but be avoided.

“We know the behaviors that drivers do that consciously and deliberately lead to 99.9 percent of every accident,” Cassell explained. “We know exactly what those conscious and deliberate behaviors are: following too closely, not looking around, not looking ahead, not communicating, not rock and rolling for turns, and not counting the kids away [after they exit the bus].”

Cassell often recommends that risk mitigation begin before a school district or bus company accepts a new driver application. In order to apply to drive a school bus, Cassell said applicants should understand and agree to follow a list of risk-avoidance behaviors.

“A safety culture is where you have norms so that people automatically do it right the first time in everything they do,” Cassell stressed. “I suggest the leadership decide what are the norms you want and communicate it.”

Between a tight budget and shallow employment pool, Kathy Furneaux worries that managers feel pressured to cut corners.

“I hear people say we are short 100 drivers, and I think to myself, I can’t even imagine it. That would have been half of my fleet when I was in transportation management,” said the executive director of the Pupil Transportation Safety Institute and a former school district director of transportation. “My fear is that they’ll start cutting corners and sacrificing the safety values that they work so hard to create because they’re feeling the pressure.”

She encouraged transportation management to identify the safety principles they value and hold on to them white-knuckled—whether that is by communicating weather-related changes, responding to an active shooter, or ensuring well-maintained equipment. “You have to have a culture of safety that is focused and rooted in awareness, and cutting-edge skill sets, in training, and having a plan,” she added.

Then, master the easy stuff. For example, eliminate simple risks, like removing telephone cords from walkways. Make sure certain staff have easy access to the superintendent’s home phone number, in case of an early morning or after-hours emergency. Walk around the bus depot and eliminate any signs of lax security. Fill potholes, fix chairs, clean the copy room.

“You know, my parents always said that everything begins at home,” Furneaux recalled.

Unfortunately, you might not notice a leaky roof at home until it rains. By then, it’s too late to keep the water out.

Kim Crabtree, director of transportation for Bend-La Pine Schools in Oregon, said she considers her district’s biggest safety obstacle the weather. Since snowstorms often result in school bus stops being delayed or moved, Crabtree invested in a smartphone app to communicate weather-related changes and road conditions to parents and drivers.

For Oregon’s fifth-largest school district, Crabtree oversees the operations of 150 buses along 80 routes that move about 10,000 students daily. To cover its tracks, the district sponsors two safety committees—one composed of two junior and two senior drivers to analyze crashes—as well as a monthly group that evaluates general campus and route safety.

Although she has fine-tuned winter protocol based on known risks, Crabtree said Bend-LaPine was recently caught off guard with an unexpected district lockdown in the middle of summer.

During its annual Kindergartner Round-Up, which is held to prepare youngsters for their first bus rides, an intruder being chased by police ran into the bus depot. Crabtree said her staff locked down the depot, and though no one else realized it at the time, she saw the holes in their plan. The procedure didn’t run as quickly and smoothly as she wanted, and some staff who were located out in the buses were difficult to reach.

“It was really good practice for us, but it just brought out some real holes in our safety around our drivers and our buses,” Crabtree said. She explained that many transportation departments tend to focus on addressing risks, where students are likely to be present while overlooking driver protections.

For Crabtree, a culture of safety is all about practice that makes the drill as realistic as possible.

“You have to just keep reinventing the wheel to deliver it in a fresh way for our drivers,” Crabtree acknowledged. “We can talk about a fire on a bus forever, and how to quickly evacuate. But we received a grant for a smoke machine, and so we do actual smoke on the bus drills, and it brings a different light to things.”

Then there is the problematic gulf that often exists between safety and risk managers. Trainers may be based in the bus depot, and risk management may be based in the school’s central office.

“Most risk managers have nothing whatsoever to do with safety training, zero,” asserted Cassell, who was previously a senior risk manager for Laidlaw. “The old way of doing risk management is identifying the risks, see if there’s a way of reducing the risks, and if there isn’t, then either transfer them—and buy insurance—or keep them all in-house through your self-insured retention.”

More often than not, Cassell said organizations not only lack incentives, but they even erect roadblocks between risk and safety management departments, although two-way communication can save lives and money.

“There should be more communication, because when you have claims, it’s worth knowing what caused the claim and if there was something you should have done to stop it,” Cassell added.

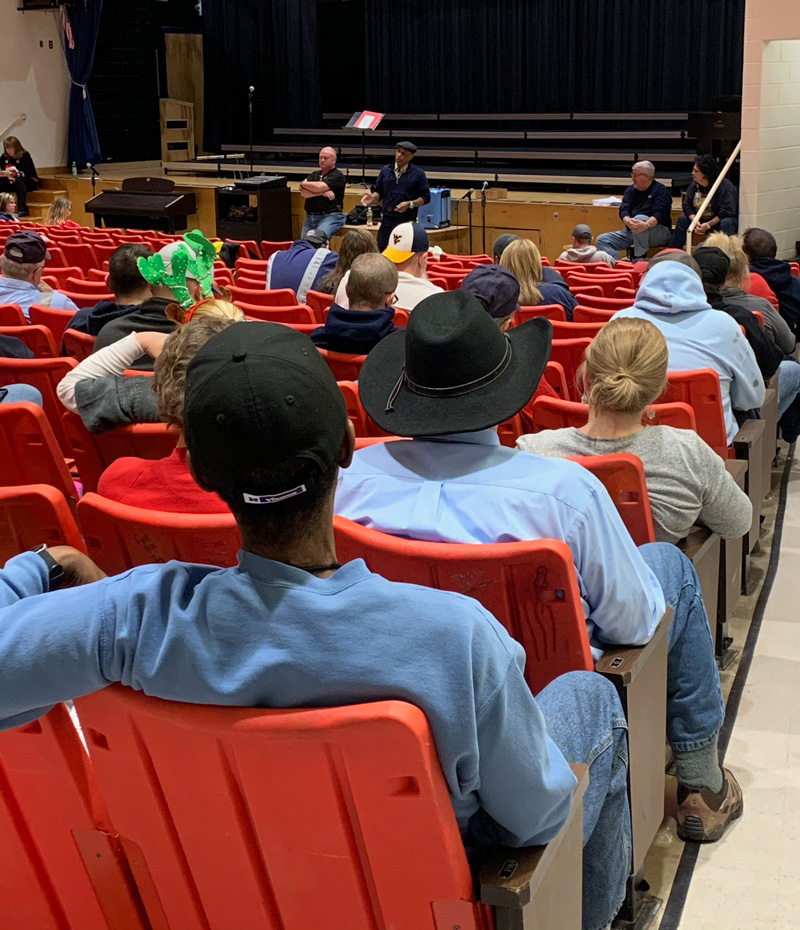

For Jimmy Lacy, supervisor of transportation safety and training for Kanawha County Schools in Charleston, West Virginia, risky crossings at busy streets were an obvious problem. But mitigating crossing risks did not happen overnight. His first step was to ensure drivers were following safe crossing procedures to a T. Kanawha employs 168 drivers and uses five facilities to operate urban and rural routes.

“We can’t quit talking about the safety of loading and unloading. That’s our most dangerous spot,” Lacy cautioned. “We can’t stop preaching how important it is to do all the required stuff. Like setting the parking brake, checking the traffic signal, and when students cross the road, check traffic and give them a thumbs up.

“We can’t get in a hurry in that process. You have to stay vigilant at that task right there, because if you screw up, it could be a child’s life.”

But even when his bus drivers and students did everything right, nearly two dozen motorists were passing buses illegally each day. To mitigate this risk, Lacy did two things. First, he eliminated the routes along busy streets, like 7th Avenue in Charleston, and sent the buses on slower side streets instead. But there was one stretch of road he couldn’t route around. So he enlisted the media to highlight the safety issue to local residents and motorists on the news.

The question that keeps Lacy up at night is what will tomorrow bring? But a safety management program that identifies risks and responds with policies that are aimed at mitigation won’t simply be the law. It can help managers, drivers and applicants all sleep better.

“If I ever have a kid that is hit and killed, I’m done,” Lacy conceded, adding that he never wants to have to ask himself if he could have done something different to protect a child’s life.